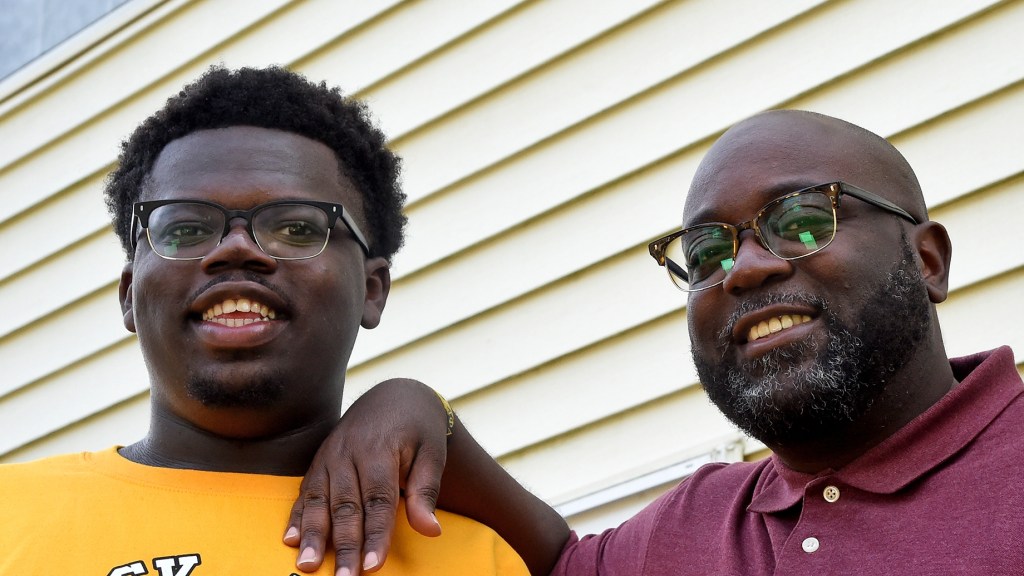

Zaire Bond always knew he wanted to be a teacher, even though most of his educators didn’t look like him.

Back in kindergarten, most of the now-18-year-old’s peers said they wanted to be a teacher when they grew up. These days, the Western School of Technology senior says he’s one of the only students he knows still planning to pursue a career in education.

Meanwhile, Zaire’s list of potential career mentors from his public school experience is thin. None of his high school teachers are Black like him. Only five of his teachers over the years have shared the same skin color as him — and the number gets smaller when Zaire considers how many were men.

“I have to be prepared that I may be the only Black teacher there,” he said about his future career.

Research shows that Black students are more likely to graduate and attend college when they are instructed by educators who look like them. Yet nationwide, Black men contribute just a fraction to the teacher workforce at about 1% for the 2020-21 school year, according to data from the National Center for Education Statistics. This was the second-lowest demographic; Asian men were 0.5% of the nation’s teacher workforce.

In Maryland, Black men account for 4% of the public schoolteacher workforce, though 17% of students are Black, according to the state Department of Education. As of October 2021, 10% of teachers at Baltimore City Public Schools were Black men, while Carroll County Public Schools had 0.4%, which translates to just seven teachers throughout the entire system. Anne Arundel, Baltimore, Harford and Howard counties counted Black men as 1% to 3% of their public schoolteacher workforce.

Zaire’s father, Anthone Bond, who is also Black, remembers his experiences in the classroom before becoming a teacher himself. He found that when the teacher didn’t look like him, the educator in the room wouldn’t call on him or ask him questions. Now that Anthone has found himself in the teacher’s seat, he said he tries to give his students the education he wishes he had gotten.

interactive_content!function(){“use strict”;window.addEventListener(“message”,(function(e){if(void 0!==e.data[“datawrapper-height”]){var t=document.querySelectorAll(“iframe”);for(var a in e.data[“datawrapper-height”])for(var r=0;r<t.length;r++){if(t[r].contentWindow===e.source)t[r].style.height=e.data[“datawrapper-height”][a]+”px”}}}))}();

“Teaching is [a] way to directly give back and influence the future,” Anthone said.

The limited number of Black male teachers stems from multiple factors, including the Brown v. Board of Education decision, which led to many Black educators from Black-only schools not being incorporated into the integrated schools; white superintendents at the time didn’t want Black educators in the authority of white students, according to an article in the Journal of Negro Education.

The issue also results from Black male students not seeing older mentors in the profession, advocates say. Pipeline programs aim to solve that issue, but programs are almost as rare as the teachers themselves. One program, the Center for Research & Mentoring of Black Male Students & Teachers at Bowie State University, a historically Black college in Prince George’s County, has helped Zaire join a supportive community of Black male teachers and students.

Bowie State professor Julius Davis founded the center in 2019 to give older students opportunities to learn about what it means to be a Black male teacher. Today, the program brings in Black male students in grades eight to 12 from across the country. The center also works on research about Black male teachers and aims to build a safe space for Black boys and men.

The U.S. Department of Education awarded Bowie State’s Black Male Educators Project a $1.5 million grant on Feb. 16, which will go toward increasing the number of Black male teachers who have the skills to help teach English for Speakers of Other Languages.

“A lot of folks that I have seen in this space, they’re looking for mentors. That is not a problem that we have, in terms of access to Black male educators or Black men,” Davis said. “And so students get the opportunity all the time to interact with folks within our local geographical region, as well as nationally, just based on who our network is.”

The Bond family has its own network of Black educators, from Anthone’s mother, Ordean Wynn Bond, who worked as a schoolteacher, to Anthone to Zaire. Anthone discovered mentors outside his family when he reached college. He decided to attend Virginia State University, an HBCU, and recognized how differently he was taught when the educator was Black. He found comfort in the HBCU family atmosphere and was inspired by the university’s initiative to fully develop all students.

At times, Anthone has let Zaire try out his teaching skills with his dad’s classes on Zoom, during which Anthone has found his son to be strict in his lessons. In between classes, Anthone poses scenarios to Zaire to pick his brain: What if a lesson doesn’t work like you want it to? How do you plan on decorating your classroom?

Some of the hypothetical scenarios Anthone throws out to Zaire relate to race and potential aggressions he could experience in the workforce. Anthone discusses with his son the importance of tact and how taking racism head-on isn’t always the best option.

“We just talk about being a Black male, period,” Anthone said.

But the conversation on being a Black male teacher doesn’t just focus on the negative. Anthone reminds his son that being a minority teacher means always being a role model. He exemplifies that to his son by teaching every student as though they were his own. Anthone helps his students search for scholarships and has even started his own in memory of his mother: the O.W. Bond Memorial Scholarship. Before she died, Anthone’s mom said she wanted to make a scholarship for students wanting to pursue education.

Zaire hopes to teach history when he gets his own classroom. His interest in the subject stems from his father, who also taught history. At home, Zaire lives with iconic Black figures like Malcom X and Erykah Badu watching from the picture frames on the wall.

Anthone recognized the importance of history because of the events he and his family experienced, especially in the American South. Living in Georgia, Anthone heard about how his dad was the one of the first kids to integrate his school. At 10 years old, Anthone attended the first parade honoring Martin Luther King Jr. in Atlanta. There, he saw the tall, pointy hats of the Ku Klux Klan standing behind him. Anthone brings these experiences and more with him to the classroom.

Today, Anthone and Zaire are living out modern history. In 2020, following the death of George Floyd, the family partook in the Black Lives Matter protests that took hold of the entire country. Anthone hopes that Zaire, like him, will be able to share these stories with his students.