A decade after Connecticut switched to the Smarter Balanced Assessment to measure academic performance, the debate about “over testing,” student anxiety, costs and “teaching to the test” continues.

Students in classrooms across the state sat down to take SBAC, the computerized English language arts, math and science test, this month, marking Connecticut’s 10th consecutive year participating in the multistate standardizing testing consortium.

SBAC fulfills federal requirements under the Every Child Succeeds Act, which calls for annual assessments in grades three through eight and in 11th grade.

Each year, educators and officials use the data as one of many factors to follow trends, monitor student growth, identify gaps in achievement, gauge whether young students are on-track for high school success, and determine if certain districts will be identified in school accountability calculations or alliance district measures.

But this legislative session, state lawmakers considered a bill that would have required the Connecticut State Department of Education to develop a plan to replace the test.

Kate Dias, the president of the Connecticut Education Association, said the proposal should remain a part of the state’s education conversation.

After state lawmakers reauthorized a mandatory audit of state and local assessments this session, Dias said she is hopeful Connecticut will have a better understanding of the “standardized testing that we are asking every child across the state” to complete.

According to the Connecticut State Department of Education, the SBAC and all its curriculum-modeled practice tests cost about $25 per student. Multiply that with the roughly 221,414 students enrolled in grades three through eight this school year and the total cost adds up to more than $5.5 million.

CSDE officials said that the SBAC lands on the cheaper side for comparative tests such as the SAT that cost about $45 a packet.

However, Dias feels many in Connecticut lack “a firm grasp on how much time we’re spending assessing students and how much money.”

“If we’re spending millions and millions of dollars on assessments, that is money that could be better spent on some of the other areas that might impact student outcomes,” Dias said. “There’s a real need for us to pause and evaluate what we’re doing and then determine what are the things that are important and what are the things that we could give up?”

“We need to get a real measure of what we’re doing with our students across the state because SBAC is just one piece of it,” Dias said.

Challenges and solutions

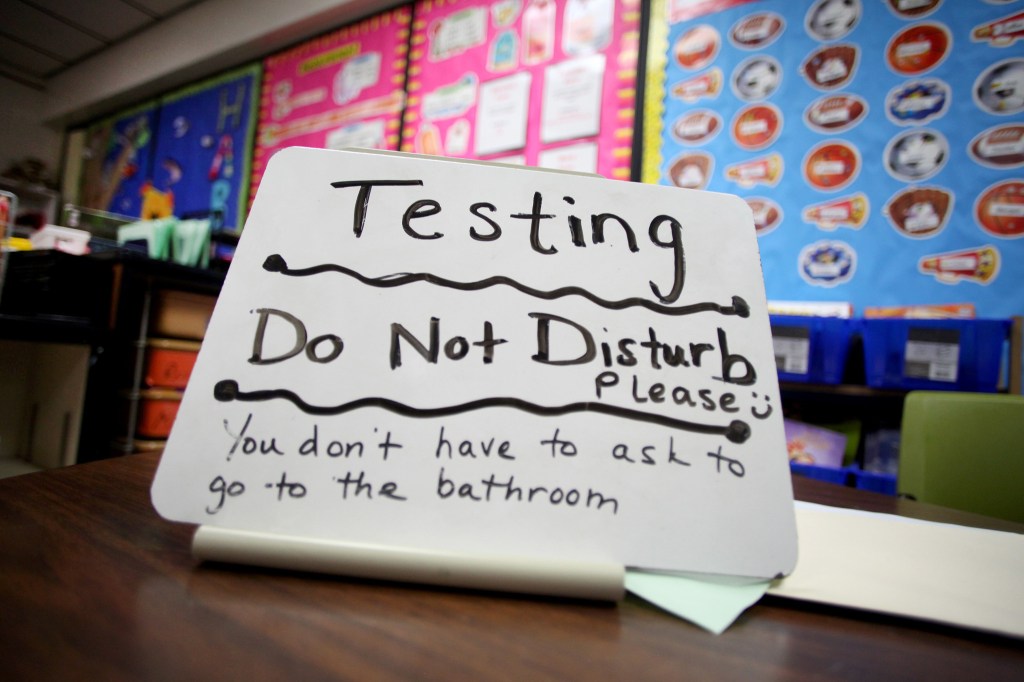

Dias and other educators identify student stress and instructional disruptions as a recurring problem during the SBAC testing period that can stretch for hours over the course of days and weeks, depending on how much time students need to complete the untimed test.

“That is an extraordinary amount of time to set aside,” Dias said “And it really creates this intensity that can often be overwhelming for our students.”

Dias said that educators agree that assessments are important, however she said that when it comes to SBAC and other standardized tests, many teachers do not “necessarily think it should be every single year.”

“I think that we in Connecticut do over assess and we could move to a space where we either did it every other year for students and we’d get the same developmental information without stressing our students so extensively,” Dias said.

Dias said that reducing the number of standardized tests, can increase the autonomy of teachers in the classroom.

“I think that if we can lessen the grip of standardized testing on public education, we’re actually going to see student outcomes improve,” Dias said.

Leslie Blatteau, the president of the New Haven Federation of Teachers and the vice president for pre-K-12 educators for American Federation of Teachers Connecticut, said the education system’s emphasis on high-stakes standardized testing is not adequately serving the needs of students.

“I think we need to be brave enough to know that almost 25 years of No Child Left Behind has not yielded the breakthroughs that people are claiming it should have,” Blatteau said.

In a post-pandemic environment plagued by attendance and achievement and mental health challenges, Blatteau said schools should invest in project-based learning models that drive engagement.

“I can’t help but wonder if the test scores would be better if we just took a three-year moratorium on that obsessive test prep and just followed what we know child development research tells us to do. We just get kids outside, make sure that class sizes are low, that mental health needs are met, that things are project-based, that things are hands-on,” Blatteau said. “I think we would be really delighted by the outcomes.”

While some may misconstrue this proposal as an attempt to lower expectations, Blatteau said such a model would actually raise the bar for educators and students through highly structured project and performance-based assessments that adopt core skills through an interdisciplinary lens in lieu of the current system’s “relentless focus just on literacy and math.”

Carol Gale, the president of the Hartford Federation of Teachers, agrees that SBAC’s rigid emphasis on math, English and science is a concern. She said the subjects are “too narrow” to evaluate the depth of a student’s education, and the various intelligences students bring to the classroom, such as artistic, musical, interpersonal and kinesthetic skills.

“Part of the drawback is a standardized test is just that, standardized,” Gale said. “It is not designed to meet the needs of individual children. It is not designed to fit the curriculum of actual individual classrooms.”

Gale said this lack of individuality can contribute to inequities when comparing scores across districts that may be at a disadvantage due to demographic factors at school or potential cultural bias in standardized tests.

“For many, many years, Hartford has had a very large number of 4-year-olds in our kindergarten classes,” Gale explained. “When you’re comparing our kindergarten classes or third-grade classes or eighth-grade classes with those of the suburbs where people may choose to wait a year … sometimes you are comparing two different age groups in standardized testing, which always is going to make the younger age group look worse.”

Instead of grade-by-grade standards, Gale said she would prefer assessments that focus on individualized growth.

“The best way to compare is to compare a student this year by what they did last year,” Gale said. “Currently, our testing is holding kids up to a benchmark of where it is expected that students at a particular grade level be. That’s a very different measure, and I would argue not as helpful for the child and not as useful to the teacher.”

Special education considerations

John Flanders, the president of Special Education Equity for Kids of Connecticut, described growth-only assessments as a “flat-out wrong” approach.

Flanders explained that the SBAC assessment and other standardized tests are critical tools for parents, educators and advocates to evaluate where the academic achievement of special education students falls in relation to their classmates. The comparison helps ensure that students with disabilities have equal educational opportunities and the same access to learning.

Flanders said that in some cases, modifications in Individualized Education Plans can allow students to progress through school without hitting necessary benchmarks for their grades, as long as they are reaching growth goals outlined in their IEP. As a result, Flanders said it is not unusual for some of his clients to be in high school but reading at a second-grade level. When this happens, Flanders said that determining the cause and what the school can do to bring the student back up to speed is crucial.

Standardized testing offers an opportunity for intervention.

“If the IEP sets unambitious goals, then it may be very easy to show growth from last year, and often is, but it doesn’t necessarily give you all the information as to where this child could or should be,” Flanders said.

While acknowledging SBAC’s challenges, Flanders said most special education attorneys and advocates agree that such tests are “really the one mechanism, the one tool we have to objectively see how the student is performing” compared to their peers.

“For kids who have challenges it can be really tough, it can be traumatizing, it can be embarrassing, but I don’t know of a better way to get the information,” Flanders said. “(We need to) explain to the student that ‘This isn’t saying that you’re doing badly, this is saying how well I’m doing teaching.’ Better communication is the answer rather than, let’s face it, what you’re describing is dumbing down the standards for a kid with disabilities.”

Even though the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act only mandates the thorough re-evaluation of students at least once every three years, Flanders said that shifting away from annual testing and moving to a biennial or triennial system is probably not the answer either.

“You can’t wait three years,” Flanders said. “If they’re in eighth grade and reading at a second-grade level, if you wait three years, they’re going to be in 11th grade, and if they’re reading at a third-grade level at that point, you have allowed a problem to exist for an unconscionably long time.”

Flanders said annual achievement data is critical to keep a pulse on not only special education students but all students during this post-pandemic period of academic decline.

“I am not a big fan of former President George (W.) Bush, but one of the things he talked about in his education plan is the soft prejudice of low expectations, and we cannot do that to our kids,” Flanders said. “We have to have ambitious expectations.”

Emphasis on growth

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the percentage of students meeting or exceeding standards on the SBAC test was 56% for English language arts and 48% for math, according to CSDE data.

Today, that number sits at 48.5% and 42.5%, respectively.

While achievement remains a significant factor, Ajit Gopalakrishnan, the chief performance officer for CSDE, said the first thing the department will focus on when this year’s SBAC scores arrive in August is another statistic — growth.

“That’s what actually gives us confidence and an indication of schools that are recovering faster from the pandemic,” Gopalakrishnan said.

According to the CSDE, in the first year of testing following the pandemic, the 2021-2022 SBAC saw student proficiency fall between five and eight percentage points in English language arts, and seven to nine percentage points in math compared to pre-pandemic levels.

But while achievement declined, growth increased — on average, students achieved 60.4% of growth targets in English language arts and 65.2% of targets in math, a 0.8% and 4.3% increase from pre-pandemic target achievement.

Unfortunately, the trend did not hold, the 2022-2023 SBAC results saw the state’s average growth rate dip below pre-pandemic numbers. However, despite the state-level decline, Gopalakrishnan said that at the local level, districts across the state continue to see significant advancements in student growth.

“There are schools even in some of our lowest performing districts, our highest needs districts, that are regular public schools that are beating the odds and growing our students at a faster rate,” Gopalakrishnan said.

Gopalakrishnan described how growth will remain a focal point as CSDE embarks on the state-mandated audit of public school assessments.

Gopalakrishnan said the intention is not to find faults within the system but to help Connecticut schools identify gaps, reduce test times, and ensure that assessments fall within the scope of their intended use and purpose.

“It’s not just the state assessments, it’s really all assessments we’re looking at,” Gopalakrishnan said. “Our goal is to reduce redundancy.”

“We need to know where kids are, we need to know who’s growing, but most importantly, we need test assessments to help teachers work with students who are not getting the content and teach in different ways so that students can learn,” Gopalakrishnan added. “That’s got to be the focus of really any assessment that we’re doing.”