Getty Images

Getty ImagesOver two nights 100 years ago, a single event transformed one of Spain’s national art forms. Brendan Sainsbury explores how the Concurso de Cante Jondo created a myth that endures today.

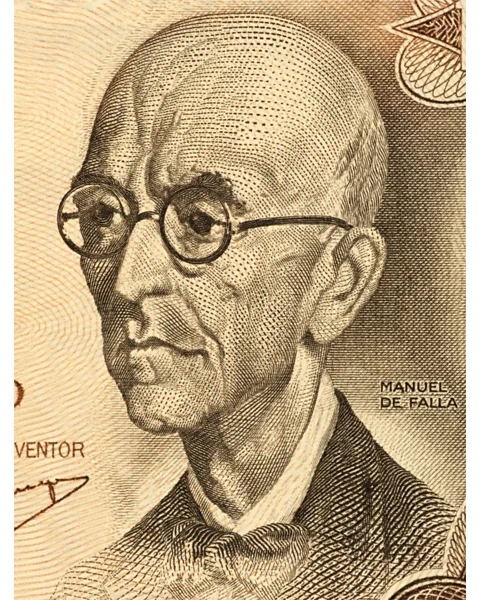

One hundred years ago, on a sultry June evening in 1922, a couple of days before the moveable Spanish feast of Corpus Christi, a stream of colourfully attired guests began to file expectantly into the Plaza de los Aljibes in Granada’s Alhambra. They were arriving for the Concurso de Cante Jondo, a flamenco singing contest that had been organised by the Andalucian composer Manuel de Falla in collaboration with a small circle of artistic luminaries that included the playwright and poet Federico García Lorca and the artist Ignacio Zuloaga.

It would have been clear to anyone in the audience that night that they were about to witness something historic and out of the ordinary. The plaza had been decorated with ornate tapestries and aromatic plants. Antique lamps glowed against the rust-red walls of the Alcazaba, the Alhambra’s 13th-Century fort, while down below, amid the slender cypress trees, women dressed in lace-trimmed shawls mingled with men in velvet jackets and Andalucian hats as they waited for the performances to start.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFalla had organised the contest with an express purpose: to elevate cante jondo (deep song) – the raw and expressive strand of flamenco practised by the Roma people – into a serious art form. The classical composer and his assembled friends were concerned that the music was in danger of losing its essence, being contaminated by popular “flamenco” which, by the 1920s had, in their opinion, morphed into a frivolous public spectacle staged in rowdy urban drinking establishments known as cafés cantantes.

Falla’s group wanted to reset the clock, opening a dialogue about what flamenco was and how it was perceived. To them, the music in its purist form was a noble art whose structure had been framed by Andalucia’s Roma people as far back as the 15th Century. Cante jondo, for Falla and Lorca, was grand, intense, and capable of inspiring a heightened state of emotion known by aficionados as duende. They revered its primitivism in the same way that Picasso revered African art, and enthusiastically integrated it into their music and poems. The problem was that, since the 1850s, flamenco had been losing its way. The music played in the cafés cantantes of Seville and Málaga wasn’t real flamenco, they argued; it had incorporated a watered-down version of cante jondo called cante chico that mixed popular song with Andalucian folklore. According to Falla, if they didn’t act to protect the music, many of its original palos (musical forms) would become extinct.

Not everyone agreed. Indeed, since the late 19th Century, many Spanish intellectuals had begun to view flamenco as regressive and cheap, the remnant of a backward-looking Spain reeling from the loss of what was left of its colonial empire in the Spanish-American war of 1898. These modernists saw flamenco as seedy and vaguely comic. Leery of its cultural value, they associated it with Spain’s myriad social and economic ills. To them, flamenco wasn’t an art, it was a form of entertainment, and a rather vulgar one at that.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAs the main organiser of the Concurso, Falla set out some important ground rules to drive his message home. Word was spread nationally and internationally about the concert’s aims, and a posse of important artists and intellectuals was encouraged to attend to broaden its cultural influence.

Crucially, Falla split the Concurso into two parts and spread it over two nights. While well-known professionals, including guitarists and dancers, were invited to showcase their talent in a wider concert, the competitive part of the proceedings was only open to amateur singers performing original cante jondo.

Although the composer was keen to ensure the concert was grand and memorable, he was also anxious to use it as a showcase for rare, half-forgotten palos and unknown rural talent. In this sense, one of the most important tasks of the event was to track down people who knew the old, endangered songs. As a result, both he and his cohorts, in particular Lorca, invested time before the concert in travelling around marginalised Roma neighbourhoods in search of flamenco in its purist form.

Over two mesmerising nights, the Concurso treated a packed audience of 4,000 to a historic musical extravaganza in an atmosphere brimming with soul and spontaneity. Memorable performers and prize-winners included Diego “El Tenazas” Bermúdez, a septuagenarian Roma man who had retired from singing 30 years earlier after suffering a punctured lung in a knife fight. Diminutive and hunched, he limped on to the stage after having allegedly walked 62 miles (100km) from his home in Puente Genil to attend the contest and proceeded to hold the audience spellbound with a rendition of a caña (an ancient song with religious overtones) sung in a fresh, almost youthful voice.

Offering a more precocious performance was Manolo Ortega, a 12-year-old Roma boy from Seville who would later be reincarnated as El Caracol, a legendary flamenco singer as famous for his lavish lifestyle as his flamboyant voice. In between, established singers and guitarists such as Antonio Chacón and Ramón Montoya entertained the crowd, and a troupe of local women stood up and danced zambras (Roma dances typical of Granada) until two in the morning. At one point, an old blind Roma woman, who had supposedly been unearthed by Lorca days earlier, took to the stage and sang an unaccompanied liviana, an ancient musical style long thought to be extinct.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAs the audience filed out at the end of the second night, many soaked after a thunderous rainstorm, most were more than satisfied. It had been an exuberant event. But, as the last stragglers hastened away from the great Nasrid palace, the debate about the concert’s wider meaning – and ultimately the meaning of flamenco – was only just beginning.

Nowadays, it’s difficult to pick up a book about flamenco that doesn’t acknowledge the influence – both good and bad – of the Concurso de Cante Jondo. The legacy of the event in the flamenco world looms large in the same way as the 1969 Woodstock festival preoccupies rock historians. Although the two events were markedly different in size and tone, both helped define their eras, spawned a cavalcade of similar events, but failed in some ways to live up to their more ambitious promises.

Like Woodstock, much of the Concurso’s enduring fame lies in who was there.

“The power of 1922 resides in the weight of the great names that directed and supported it, above all Falla and a very young Lorca,” says José Javier León, a writer and professor, and author of a 2021 book about the Concurso called Burlas y Veras del 22.

As for its positive benefits, the 1922 concert inspired a number of subsequent concursos all over Spain, most notably the Concurso de Córdoba in 1956, and others in Seville, Huelva, and Madrid. Falla’s event also succeeded in uncovering new talent (including the flamenco legend that was to become El Caracol) and saved several old flamenco styles – notably the martinete and liviana – from almost certain extinction.

“I think that the Concurso set a precedent for competitions in the profession which definitely changed the way we perceive flamenco and to a degree how we value it,” says Magdalena Mannion, a flamenco dancer who trained at the Amor de Dios dance school in Madrid. “Was it successful in its attempt to preserve the purity of the art? I don’t think so – I think what it did was start a process in which to quantify and compare something that is so personal it should be difficult to judge by numbers.”

These days, modern observers are prone to question some of Falla’s and Lorca’s historical assumptions, in particular that flamenco in the 1920s was decadent and dying.

“Flamenco from its origins was an urban manifestation,” states León, “Not rural and secret, as the promoters of the Concurso believed, not a handmade product of any aficionado, but a complex artistic discipline. They divided the flamenco tree in two, on one side cante jondo with only positive connotations, and on the other “flamenco” – derivative, adulterated, and commercialised. This division was pernicious.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesLeón suggests that many of the concert’s ultimate “achievements” had the opposite effect to the organiser’s original intentions, something he refers to as “a fertile error”.

“Contrary to its own principles, the competition ended up benefiting [popular] flamenco,” he explains. “It widened its format, prompted the recording of musical styles that might have been lost because of their weak commercial pull, and heralded subsequent flamenco festivals that were attended purely by professionals.”

Perhaps the biggest criticism of the Concurso was that it elevated cante jondo above everything else and, in the process, failed to recognise flamenco’s other vital strands, such as Andalucian folk music. Falla and Lorca were indulging in a rescue fantasy, critics opine, obsessed with musical purity over healthy cross-fertilisation.

“Lorca contributed a huge amount to the flamenco world,” says Mannion. “But I also think he, and others in that more intellectual circle, romanticised flamenco too much in a way that puts the concept of ‘purity’ before the life and needs of the actual artist.”

León concurs. “There is a mantra that has accompanied flamenco since its birth and that won’t go away. ‘It is in grave danger, it is dying, we have to save it! Help!’ The Concurso recovered this moribund idea and amplified it.”

Art isn’t a static medium. It evolves and takes on new influences over time. Across numerous millennia, painting morphed from prehistoric cave etchings to the Mona Lisa. The Beatles progressed from Love Me Do to Sgt Pepper in a mere five years, yet no one claimed their later songs were inauthentic or impure. Even cante jondo is a product of a complicated musical journey that started in India absorbing Hindu, Byzantium, Jewish, and Moorish influences on its way to southern Spain.

“I feel like the biggest problem with flamenco are the questions with a yes or no answer,” says Mannion. “‘Is it or is it not flamenco? Is it authentic or is it not?’ We need to shake this off – at least as artists and audiences. ‘Did I like it, did it make me feel something?’ I think that’s a better question.”

In the years that followed 1922, flamenco didn’t purge itself or revert to cante jondo at the expense of all else. Instead, tastes fluctuated wildly. With the onset of the Civil War and the Franco regime, the art was initially disavowed as crude and un-Catholic but later revived when Spanish authorities used it commercially as a lure to draw in foreign tourists.

By the 1970s, the music was tugging in many different directions: on the one hand it had become heavily commercialised and inclusive of different interpretations; on the other it remained a respected and much-studied classical art that was declared an Intangible Cultural Heritage by Unesco in 2010. The two great flamenco geniuses of the ’70s and ’80s, the guitarist Paco de Lucía and the singer Camerón de la Isla, mined the music on many different levels, drawing deeply on cante jondo, but also introducing new innovations such as keyboards and electric guitars. By the 21st Century, flamenco had evolved into a world music, fusing intermittently with jazz, rock, blues, and rumba.

If the Concurso of 1922 taught us anything, it’s that flamenco is complicated and organic, and has prospered through constant evolution. Cante jondo is an essential link in the music’s family tree, but it’s not the only one.

On a magical June night in the Alhambra, Falla and the others staged an epic event. They brought flamenco into the public sphere, piqued the interest of previously reticent intellectuals, and sparked a vociferous debate that is still raging today. “The Concurso generated a surge of creative energy and a poetic myth,” says León, “And no art scorns the enormous power of mythology.”