(Photo by Warren Wong)

Over the past few years, more and more funders with free-standing, endowed, or well-resourced private philanthropies have reached out to us asking us for help connecting them to potential co-funders. The pattern has often been this: The philanthropist is starting up or scaling an innovative program that will transform that field, and they want to attract peer partners to join them in supporting their initiative. At first, they describe it as “co-funder acquisition” or “resource mobilization” or “seeking philanthropic partners,” but eventually the word “fundraising” pops up. At some point, we realized we were witnessing a new trend: funders fundraising.

Not including stand-alone entities whose primary purpose is to fundraise from multiple donors, we have so far identified at least 10 major philanthropic organizations that have staff who dedicate part or all of their time to mobilizing resources toward their organizations’ missions—and there are likely more. Our analysis of and work in this area has helped refine our understanding of how this approach emerged; how it differs from other approaches, including donor collaboratives; and its benefits and challenges. Here, we aim to help philanthropists interested in adding this form of “getting” to their giving activities determine whether and how to incorporate it into their work.

Amplifying a Funder’s Mission With Fundraising

In the past couple of decades, many funders have shifted their attention away from single-issue areas to solving one or more complex societal problems, often using a combination of philanthropy and investment capital. In the process, they’ve recognized that problems like climate change and racial justice are too big to solve alone. A sense of urgency to address large social problems—and frustration with the fragmentation of philanthropic giving broadly—has pushed many of these funders to explore new ways of validating and amplifying their giving strategy.

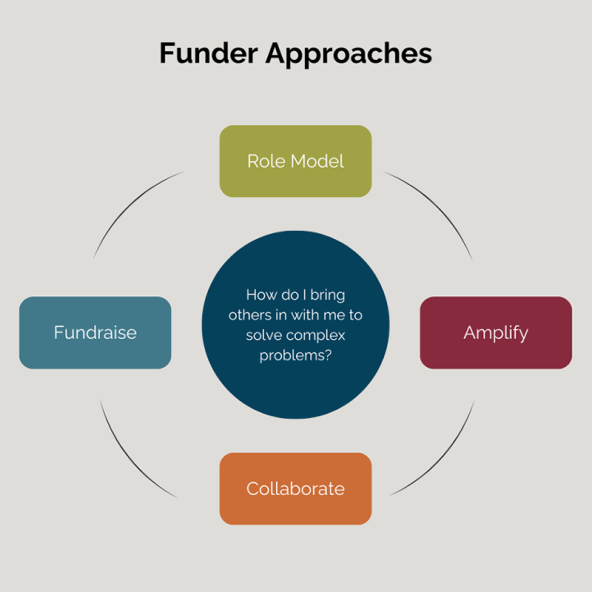

Four common approaches to amplifying a funder’s approach. (Image courtesy of Sofia Michelakis)

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR’s full archive of content, when you subscribe.

Common approaches include funders focusing on their own grantmaking, believing that good work speaks for itself and others may follow

(role model); encouraging public awareness, policy changes, and/or new government funding for causes or grantees they care about (advocate); and joining a collaborative effort

with a group of donor peers and a co-developed action plan where they all share outcome goals (collaborate). However, actively getting resources from peer funders to augment one’s own theory of change and grantee portfolio (fundraise) is relatively new.

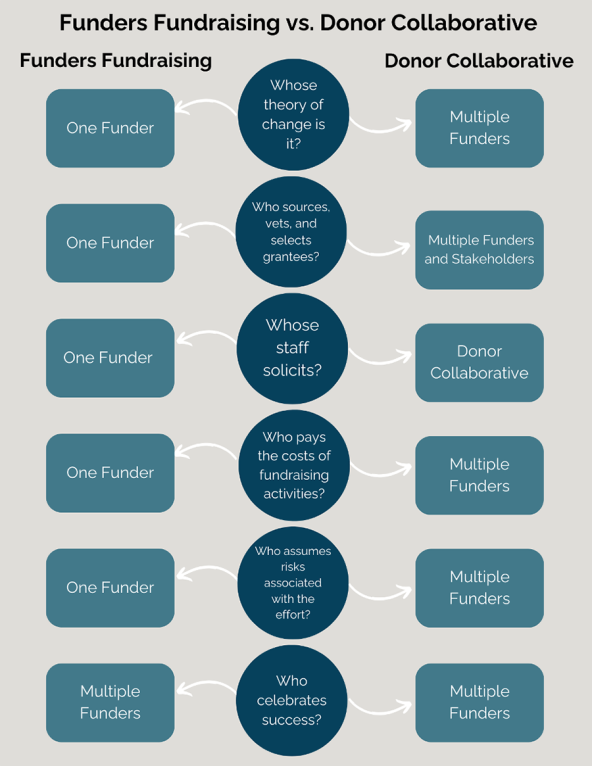

This fundraising approach differs from donor collaboratives in several respects. For one, it starts with one funder’s theory of change, and that funder makes the decisions, staffs the fundraising activities, and bears the risks of the effort not succeeding. Another important difference is that peer funders don’t have input on sourcing, diligence, or selecting grantees. The following table compares the two:

Differences between funders fundraising and donor collaboratives. (Image courtesy of Future Science Now)

We’ve seen philanthropists actively fundraising at three different stages of the funding lifecycle: seed, growth, and last mile. Here are a few examples:

- Seeding a new initiative. Schmidt Futures advances its strategy by seeding projects, such as the scientific incubator Convergent Research, that are then poised to absorb follow-on funding. Its in-house scientific team sources, vets, and launches programs that present credible co-funding opportunities for both new and established funders. Tom Kalil, Schmidt Futures’ former chief innovation officer, told us, “We can de-risk projects by being the seed funder and then encourage a new philanthropist to jointly fund a project.”

- Building, growing, and sustaining a proven program. In a Washington Post interview, Raj Shah, president of the Rockefeller Foundation, explains how he and his team scaled a proven renewable energy program, in part by raising money from the Bezos Earth Fund and the IKEA foundation. Each of the three funders gave $500 million to expand Rockefeller’s Smart Power India program from 1 to 20 countries under the Global Energy Alliance for People and Planet initiative.

- Funding the last mile. Sometimes funding is needed to push a challenging project through the “last mile” and across the finish line. A classic example of last-mile funding is in efforts to end disease. After making the eradication of polio one of its top organizational priorities, The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation created the Polio Eradication Fund as a vehicle to engage additional funders. Bill Gates has personally sought contributions from other philanthropists for the fund, putting his weight behind the initiative and communicating directly with funders he has recruited to keep them updated on progress.

Benefits of Funders Fundraising

Done thoughtfully and effectively, funders fundraising can provide several valuable benefits. This approach is beneficial in cases where an influential philanthropist or foundation has taken the lead on building infrastructure to support a specific social or health solution, and it would be difficult or duplicative for other donors to act individually, particularly in a crisis. In 2020, for example, the Gates Foundation used its expertise on fighting infectious diseases to enable Gates Philanthropy Partners, which accepts funding from other donors, to rapidly source, vet, and select essential infrastructure funding opportunities for a new Combatting COVID-19 Fund. This fund channeled $90 million to 30 grants in a matter of months, allowing grantees to expedite vaccine research and development, and disease surveillance.

As with donor collaboratives, fundraising can also validate a strategy. Funders can pressure test their work by inviting other funders to contribute to a particular initiative; if peer funders review the proposal with a critical lens and decide to support it, it’s a marker of the soundness of that strategy. The Omidyar Group, which includes a range of philanthropic organizations and initiatives, points out that one of the rationales for seeking new funders to join their mission is so that they can test new ideas. A funder fundraising around early-stage ideas often mirrors a venture capital approach, which aims to flesh out potential solutions to a problem and increase the chances that the best solutions will move forward.

Funders fundraising can also open up vetted giving opportunities. New philanthropists and philanthropists expanding into new program areas particularly benefit from partnering with and tapping into the expertise of peers during the process of selecting grantees. Skoll Foundation, for example, shares leads and due diligence information with funders and strategic partners, and connects them with social innovators doing groundbreaking work. As CEO Don Gips shared with us, “One of the most important things we can do for the social innovators we fund is to share with other funders, as well as with partners across sectors, the great work that led us to fund them.”

A fourth benefit of funders fundraising is that it helps address what many critics see as a lack of charitable capital flowing from the ultra-wealthy. Hilary McConnaughey, associate director of the Center for Strategic Philanthropy, and her former colleague Sokol Shtylla explain that many people want to activate the “unprecedented amount of dormant capital sitting on the sidelines [that] could be working to achieve long-term, life-changing gains all over the world.” One funder’s enthusiasm for a project can inspire others to put capital they would otherwise not move into use.

Challenges of Funders Fundraising

For all these benefits, fundraising also comes with risks for philanthropists and the social sector. One is that it may divert funding away from other important areas. High-net-wealth individuals often trust their peers more than they trust nonprofit leaders, who are experts in the field. Gretchen Phillips, managing director of Omidyar Network, stated, “We are clear-eyed about the risks inherent to pooled philanthropic funds—among them, that the resources used to fulfill fund commitments might be diverted from existing programs and their associated grantees.”

This can also mean even less investment in systematically underfunded organizations, such as Black- or women-led social enterprises. Data clearly shows that funders award larger grants to white-led organizations

and that white-led organizations are more likely to receive unrestricted funding. Put another way, if a well-known philanthropist persuades four peers to channel funding through their own strategy, grant-seeking organizations that may have had five funders to approach are left with only one. This aggregation of funds may elbow out other viable strategies and create further disparity by concentrating power in the hands of the philanthropist who successfully solicited the additional funders.

The credibility of funders fundraising is another common risk, only the stakes can be even higher for single funders fundraising. One funder we observed became so enthusiastic about an organization he supports that the donor he was trying to recruit to his cause excused himself from the conversation. The latter said he felt so overwhelmed by the pressure to sign on that he couldn’t concentrate on understanding the work of the grantee his peer was so adamantly describing. Jennifer Kitt, president of Climate Lead, advises, “Be a peer, don’t pitch your own thing too hard because you will lose credibility both with your peers and in the field.”

Finally, funders risk public scrutiny about why they’re fundraising in the first place, rather than increasing their own payout instead. As Oxfam has reported, billionaires are $3.3 trillion richer today

than they were in 2020. However, the vast majority of billionaires, even those with the stated intent to be generous, have given less than 5 percent of their wealth to charity, according to Forbes. Accordingly, we’ve heard many people look at well-resourced foundations fundraising and ask, “Why can’t that foundation just fund the whole initiative?” This is a valid perspective, and worth considering in cases where philanthropic entities and individuals can afford to increase their annual giving.

Deciding Whether to Begin Fundraising

As these benefits and challenges suggest, fundraising can be a productive avenue for social good, but it isn’t suited to everyone. The following four steps can help funders evaluate whether it’s worth pursuing.

1. Get clear about goals. First, make sure you’re working on behalf of what the public needs, not just following your own pet project or a charismatic expert’s shiny new idea. Fundraising is best suited for strategies that are clear, measurable, and attainable. Ask: How, specifically, will this approach further a critical social or scientific mission? Also, consider your time horizon, and whether the goal is to fundraise for a one-time program or create a community of funders who will give repeatedly. The answers to each of these considerations will dramatically influence the feasibility and infrastructure you need to succeed. An example of a time-bound project is when Patrick Collison, cofounder and CEO of the fintech company Stripe, and others inspired by him, fundraised from peers to support Fast Grants, a program that relied on external due diligence to push funding into urgently needed science and technology projects during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Engage the community.

Take the time to ask grantees and others affected by the problem you’re addressing what they want, and use a third party to conduct interviews, an anonymous survey, or another method that enables honest input. We recently conducted confidential interviews with a broad set of grantees and other philanthropists to help a funder assess whether these groups supported the funder’s potential fundraising efforts. The interviews also pinpointed major challenges for grantees in their own fundraising efforts and how they wanted the funder to engage with them. In the case of funders fundraising for a specific cause or mission, it’s often best to introduce grantees to prospective donors and then get out of the way so that grantees can build their own relationships.

3. Assess internal fundraising capabilities. The skills, systems, experience, and effort required to mount a successful fundraising operation are well-established and available, but not always built into operations. It’s important to consider which staff would be responsible for fundraising, creating marketing materials, and monitoring a potential donor database. Hiring a development professional who has experience with peer-to-peer fundraising can help you determine the feasibility of your vision, and build the systems and capacities you need.

4. Consider alternatives. Conduct a full field scan to identify donor collaborative efforts

or leading nonprofits in your sector that you could support. This will help you determine whether fundraising is truly the best way or the only way to further your mission. Use your networks and resources to engage with peer groups such as Health Research Alliance, Giving Compass, Philanthropy Together, and P150, and determine whether there are efforts underway in your areas of interest.

Effective Practices for Funders Fundraising

It’s not yet common practice, but for those who decide to fundraise, the first thing to do is ask other funders about their experience, including their starting and ongoing costs, and how to avoid any obstacles they encountered.

Next, focus on equity. This includes taking the responsibility of fostering equity in your funding portfolios seriously. Allocate resources

to reaching new networks, expand grantee applicant pools to include historically overlooked communities, and make larger grants. The Heising-Simons Foundation

is a notable example of a funder that’s explicit about how it’s translating its commitment to equity into actionable grantmaking practices.

Fostering equity in your fundraising practices also includes mindfully investing in talent. Most foundations recruit program officers because of their expertise in a particular field, but these individuals rarely have a strong understanding of the fundraising process and the nuances of relationship management. Adding a new directive to raise money creates a new set of expectations and responsibilities for staff, and requires training and/or new hires. If you hire new staff, consider the impact on grantees and other stakeholders. Is there a way to hire without drawing talent away from your grantees or the field you hope to build through fundraising?

Having the right staff on board will allow you to take a relational rather than a transactional approach. Transactional fundraising usually involves lower monetary values and shorter lead times before solicitation, while relational fundraising usually requires a longer-term cultivation process with the goal of securing larger gifts. Trained fundraisers know that people give to people. They can advise on how and when to make an appropriate ask and, equally important, maintain relationships with donors after they make a gift.

It’s also important to be transparent and accountable to grantees and others you hope to benefit. This is especially important for funders who engage in fundraising, because they will be giving away other people’s money in addition to their own. Most foundations with living donors have small, tightly held governance structures that primarily reflect the lived experience of a philanthropic individual or family. This prompts the common critique that philanthropic dollars are heavily subsidized by society

and that philanthropic institutions should be more accountable to communities. Including community members in decision-making is one concrete way to build accountability and gain new perspectives on your approach.

Time will tell whether private funders fundraising becomes a permanent part of the philanthropic landscape. We hope that funders who decide to actively fundraise do so only after very carefully evaluating the implications on their grantees, their peers, their own organizations, and their sector. Moreover, funders should engage in fundraising with transparency, full awareness, and appreciation of well-established fundraising practices.

Indeed, one fruitful outcome of this approach might just be more empathy for the challenges of fundraising and the balancing act that nonprofit grantees commonly face: caring for donors plus doing the mission-driven work. Fundraising is relentless work and more an art than a science, and recognizing the value and challenges grantees experience in doing it may lead to stronger partnerships overall.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Valerie Conn & Sofia Michelakis.