(Illustration by iStock/smile3377)

Nonprofit leaders often grapple with the question of how big their organization will need to get to have the impact they aspire to. Inevitably, that question is coupled with the question of where the money will come from to support that growth.

“That is always top of mind, the question of how you sustain it, build it, grow it,” says José Quiñonez, CEO of the Mission Asset Fund (MAF), a 16-year-old organization that works to create a fair financial marketplace for immigrants, particularly those who are undocumented.

In the 2007 SSIR article “How Nonprofits Get Really Big,” our Bridgespan colleagues William Foster and Gail Perreault identified US-based nonprofits, founded within the previous 30 years, that had reached at least $50 million in annual revenue. Limiting the age of nonprofits in their data to a 30-year span ensured they were able to identify instances where organizations “found their funding model” and scaled relatively rapidly. It also established a clear starting point from which revenue growth could be measured. The data showed that over 90 percent of these “really big” nonprofits “raised the bulk of their money from a single category of funder such as corporations or government—and not, as conventional wisdom would recommend, by going after diverse types of funding.” Conversations with leaders at these nonprofits underlined that achieving scale had required fundraising teams and capabilities that were tailored to the needs of their primary funding sources.

Now, with much having changed in the social sector over the past 17 years, we wanted to know—Did the original findings still hold? This article is based on a new analysis of the 297 US-based nonprofits founded since 1990 with over $50 million in annual revenue in their most recently available audited financial statement or IRS Form 990. We will refer to this group of 297 nonprofits as “all large organizations” below. We also interviewed the leaders of more than a dozen of these organizations to describe our findings and the implications for nonprofits and their leaders, particularly those seeking scale.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR’s full archive of content, when you subscribe.

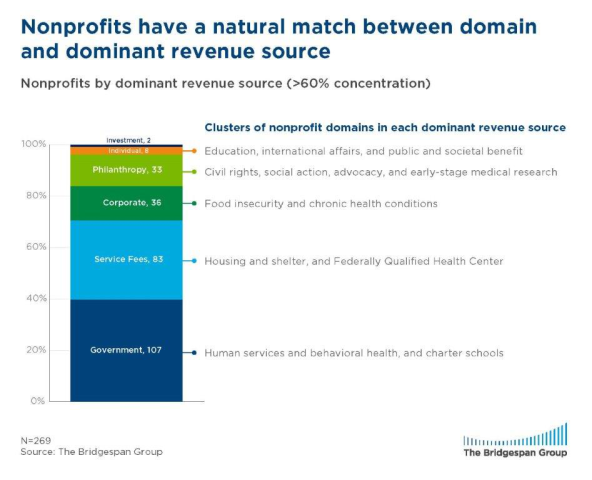

The headline is that these organizations grew to their current size mainly by focusing on a single revenue category rather than diversifying across categories of funding. As with 17 years ago, over 90 percent of the organizations in our study—269 of them—had a dominant revenue category which accounted for at least 60 percent of the organization’s total revenue. We predominantly focus on those 269 organizations in this article—sometimes referred to as our “data set.”

The three most prevalent funding categories in 2007 remain so today, and in the same order: government, program services/earned revenue, and corporate. And a secondary revenue category can still be important to many nonprofits’ growth and sustainability. (See Figure 1.)

The biggest difference today is that philanthropy—meaning gifts of $10,000 or more from foundations and individuals—now functions as the dominant funding category for a meaningful share of large US-based nonprofits. In 2007, there were just two nonprofits in the data set that had philanthropy as their dominant revenue category, accounting for less than 2 percent of the nonprofits studied with a dominant source. In 2023, this rose to 12 percent of the data set—33 nonprofits in all.

This time around, we also took account of the racial and ethnic identities of the leaders of the large nonprofits. What we found is that, of the 297 large organizations founded since 1990, 27 percent have a CEO or executive director who identifies as a person of color. These are organizations that have found ways to make headway against the racial bias in philanthropy faced by leaders of color. More on that later.

This article delves deeper into our headline finding to discuss three especially important practices for nonprofits that want to raise the money to achieve significant scale:

- Focus on concentration in one or two revenue categories.

- Seek funding that is a natural match for your organization’s work.

- Build dedicated capabilities and infrastructure to tap into the one or two revenue categories you’re focusing on.

Why Grow Big?

At Bridgespan, our team members have been fortunate to work with and learn about a wide range of nonprofits that are doing important work. Many of them have annual revenues significantly below $50 million—some a few million dollars or less. Often, size is not commensurate with impact.

Most nonprofits do not seek to get really big. Still, even for those that seek to sustain themselves at a smaller scale, it may be important to focus on one or two main revenue categories and build the capabilities needed to achieve that focus.

Organizations that do seek to get big have in common a belief that greater scale is critical to achieving the impact they seek and the good fortune to tap into major funding categories (like government, which is the dominant revenue category for 40 percent of the nonprofits in our data set).

The leaders we interviewed for this article are not simply intent on growing for the sake of growing. For all of them, growth has been critical to achieving their goals. Some aspire to grow more, others seek to sustain their current size, and a few tell us that a slightly smaller level of annual revenue might ultimately be more sustainable than where they are now. Though this article is mainly about how nonprofits grow large—the why will always be a critical question for leaders.

Focus on Revenue Concentration, Not Diversification

We identified 297 nonprofits founded since 1990 that reached at least the $50 million mark in annual revenue, compared to the 144 identified in the 2007 study. This increase in our data set seems generally in line with the overall growth of the social sector, paralleling the growth of government and philanthropic spending, in the intervening years. (We kept the $50 million revenue threshold rather than adjusting for inflation. Even today, $50 million is a lot of revenue, and we were happy to have a larger data set to look at.) Nearly half of the 297 organizations are in education or health care, including 67 charter school organizations and 25 federally qualified health centers.

Over 90 percent of the 297 nonprofits with $50 million or more in revenue had a dominant category of revenue—and on average that category accounted for 90 percent of total revenue. These statistics are unchanged from our 2007 study, showing a remarkable consistency on this fundamental rule of how nonprofits get big. It is concentration on a single revenue category, not diversification across multiple categories, that is overwhelmingly the path to growth.

We should be clear here—by concentration we mean focus on a category of revenue source, such as “government.” Within that category, organizations will often pursue multiple sources of government revenue.

While concentrating on a dominant revenue category is important, as the 2007 study found, sometimes a secondary category is also valuable. Around 30 percent of the 269 nonprofits in our data set have a secondary revenue category that accounts for at least 10 percent of its revenue. When an organization’s budget is $50 million or more, such a secondary category brings in millions of dollars. For many of these organizations that secondary revenue source didn’t just spring up recently. It developed alongside the primary source—so that the organization becomes a sort of hybrid vehicle, built to run on two different types of power.

Seek Funding That Is a Natural Match for Your Organization’s Work

Becoming a large organization almost always involves pursuing a dominant revenue category that is a natural match to the organization’s mission, activities, and populations of focus. We will illustrate some examples of natural matches as we go through each of the key revenue categories.

Government: Of the organizations in our data set with a dominant funding category, government—federal, state, or local—is the dominant revenue category for 40 percent of them. Almost half of these organizations are in education or human services, representing a “natural match,” whereby governments contract with or provide grants to nonprofit agencies for services that government typically funds but does not always provide itself.

Governments also are a source of revenue for other nonprofits that are not traditional direct service providers. Consider the example of the Center for Sustainable Energy (CSE), a national nonprofit that accelerates adoption of clean transportation and distributed energy. Founded in 1996 in San Diego, CSE now works in a dozen states for state and local governments and utilities. Approximately 80 percent of CSE’s revenue comes from state government contracts to design and administer clean energy and transportation programs.

“Some time ago we figured out what we do really well and who would pay for it,” says Lawrence Goldenhersh, CSE’s president. “We were experts at managing programs, especially large market transformation incentive programs where we could do some planning and leverage our data. Within a state we can tap into a variety of government revenue sources, which provides financial strength and stability.”

While few if any of the large nonprofits in our data set do the same kind of work CSE does, and most of them don’t need to compete with for-profit enterprises, its basic funding strategy applies to most large nonprofits. Figure out what you do well, figure out who will pay for it, and become experts at tapping into that funding source.

Program services/earned revenue: This is the primary revenue category for 30 percent of the nonprofits in our data set. These nonprofits work in a wide range of fields, but almost all of them offer services for which people are willing to pay to receive. (Bridgespan itself—which is in the data set of large nonprofits founded since 1990—gets approximately 70-80 percent of its revenue from fees paid by clients for its advisory services. We also have a significant secondary source—philanthropy—which helps us research and write articles like this one, which are provided free to the social sector. Bridgespan has had the same funding model—earned income as primary, philanthropy as secondary—since its founding in 2000.)

Almost two thirds of the organizations in our data set that rely on earned revenue as their dominant funding category are in the education or health care sectors. These sectors are a “natural match” for earned revenue as the main funding source. (In some cases, they might also be a natural match for government funding.)

A match may be “natural” but it can sometimes require a great deal of time and effort to develop. Consider the example of One Acre Fund, a global nonprofit registered in the US that supplies farmers in sub-Saharan Africa with the farm supplies and training they need to grow more food and earn more money. Beginning in 2006 with a pilot that served 38 farmers in Kenya, it now works with over four million farmers in nine sub-Saharan countries.

“One Acre was designed from the start to rely mainly on earned income,” explains Matt Forti, the organization’s managing director. It provides farm products on credit, which farmers repay over the growing season. It also trains farmers on effective agricultural practices and how to sell any harvest surplus. “We always knew we would charge farmers for our services. We want them to be our boss.”

Though it had its eyes on earned income, One Acre Fund had to rely a lot on philanthropy in its early years. It still raises significant funds from philanthropy, but the trend is clear: in 2015, earned income made up 43 percent of the organization’s revenue; by 2022, it had risen to 65 percent. “It’s been crucial to have this dual revenue stream,” says Forti. “In our larger markets, we don’t yet cover 100 percent of our program costs with earned revenue—but there is a path that comes close to 100 percent. Where philanthropy comes in is that it helps us grow and serve new farmers and new countries. And some of the poorest countries where we work in may always need a philanthropic subsidy.”

Corporate: Though far behind government funding and earned income, corporate gifts are the third largest revenue category, accounting for 14 percent of organizations in the data set. Most organizations in this category rely more on in-kind contributions than cash—mainly in the form of material goods (like food or medical supplies) but sometimes services, as well (like advertising space). A quarter of organizations in this category tackle food insecurity, like Farmer Frog, which supports distribution of farmer-donated produce across the US, including to Indigenous communities. Other examples from our data set include First Book (donated supplies help it provide books and other resources to children in need) and Digital Promise Global (donated internet service plans help it expand learning opportunities and address historical exclusions in education). Some organizations in this category do receive substantial cash donations from corporate supporters. For example, donations from pharmaceutical companies allow Good Days to help individuals diagnosed with chronic conditions access treatments and services.

Individual giving: Small giving, that is, amounts of $10,000 or less, comes in fifth at 3 percent of the dataset. These are typically nonprofits working in areas that directly touch a lot of people and secure broad individual support. For example, DonorsChoose provides an online platform for individuals to support teacher projects in public schools. Since its founding it has raised $1.64 billion from millions of individual donors to support projects in almost 90,000 schools. Also funded mainly by smaller individual gifts, Smile Train supports cleft surgery and other forms of essential cleft care in 87 countries across the globe.

Investment income: Two organizations relied on investment income as their dominant funding category, including The Truth Initiative which received a large financial settlement from tobacco lawsuits. Traditionally, income from an endowment or other investment vehicle was only reserved for a privileged set of universities, hospitals, and arts institutions. This may be starting to change. Indeed, there are increasing calls to fund endowments for social change organizations, especially for the Black-led organizations where endowments are rare (see “Endow Black-Led Nonprofits”).

Philanthropy Is Now a Significant Revenue Category for Large Nonprofits

A new entrant among significant primary revenue sources for large nonprofits is philanthropy—gifts of $10,000 or more from both foundations and individuals—which comes in fourth at 12 percent, just behind corporate giving but well ahead of individual small-donor giving. Here’s what the 2007 article had to say about philanthropy as a funding model:

The least frequent source of funding for high-growth nonprofits is foundations, which are the primary funders for only two of the organizations in our study. … In general, foundations seem to be more focused on their traditional role of starting new programs rather than supporting them at scale.

Times have changed. Philanthropy is the dominant revenue category for 33 large nonprofits in our data set.

One big question about the rise of philanthropy as a dominant revenue category for large nonprofits is whether it is a trend or a short-term phenomenon. For example, could the $17.3 billion in gifts to more than 2,300 nonprofits by MacKenzie Scott and her Yield Giving

philanthropic vehicle starting in 2019 (through late May 2024) have changed the primary revenue source for nonprofits in our study? In reviewing publicly available data, we found that 38 of the 297 large nonprofits—approximately 13 percent—had received a gift from Scott. This includes 10 of the 33 nonprofits with philanthropy as a primary revenue source. However, we were unable to identify any organization in our data set whose primary revenue source switched to philanthropy as a result of her gift.

In fact, these larger nonprofits that rely on philanthropy saw a remarkable stability in their dominant revenue category. Looking back 10 years, 28 of these organizations were in existence and all but one already had philanthropy as their primary revenue source. The evidence seems clear: philanthropy as a funding model is a longer-term trend, not a momentary blip.

This change has been fueled in part by philanthropy itself. Interviewees tell us that donors have been writing larger checks and staying at the table longer. “When I came to PolicyLink in 2011 $250,000 was a big gift for us,” explains president and CEO Michael McAfee. PolicyLink is a national organization advancing racial and economic equity. “Now the average gift is $750,000 to $1 million. And we are getting some gifts that are much larger than that. The scale of what we want to accomplish for the nearly 100 million people in America struggling to make ends meet warrants investments of this magnitude. And we see funders staying with us for longer.”

About half of the 33 large nonprofits with philanthropy as their dominant revenue source, including PolicyLink, have an executive director or CEO who identifies as a person of color. Many of these CEOs of color lead organizations focused on equity, justice, or social reform work—for which there may be a unique role for philanthropy to identify and sustain such investments.

Even with the natural match, those leaders have had an uphill climb. Several years back, Bridgespan partnered with Echoing Green to analyze organizations applying to Echoing Green’s prestigious fellowship. That analysis found that on average the revenues of the Black-led applicant organizations are 24 percent smaller than the revenues of their white-led counterparts—underlining that the barriers to fundraising and scale for organizations with leaders of color are real and pervasive.

Some leaders of color discussed how they have been able, at least in part, to address those barriers. McAfee told us it was fortuitous that his predecessor, Angela Glover Blackwell, was a Black woman. He believed her presence made donors more open to his leadership when otherwise people can be “uncomfortable with my race, my passion, and my unwavering conviction to do liberating work.”

Another organization for which philanthropy is a natural match is the Mission Asset Fund, with its work to create a fair financial marketplace for immigrants. In 2007, the Levi Strauss Foundation and a group of community leaders used a $1 million investment funded by the sale of the last Levi Strauss denim factory in San Francisco to create MAF. But, says CEO José Quiñonez, the organization did not become big overnight. “We built our own processes and technologies for the lending circles [its key loan program], and our budget was around one million [dollars].” In time, MAF moved beyond its focus on San Francisco’s Mission District, where it was founded and where it is still headquartered. “We built a network of providers across the country to reach other communities. Then a crisis hit.”

When the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program ended in 2017, people in the program had just 30 days to reapply. MAF tapped into philanthropic donors to help use its technology platform directed at immigrants to help with DACA renewals. And MAF turned to philanthropists again during COVID-19 to help it to dramatically increase its emergency grants program. Though MAF also saw opportunities to tap into government revenue during the pandemic, it passed them up. While government funding might be a natural match for the type of work that some immigrant-serving organizations do, MAF saw it as a potential conflict for its own work, which serves so many undocumented people.

The experiences of PolicyLink, MAF, and other large organizations whose dominant funding category is philanthropy suggest that a new generation of nonprofits is demonstrating its capacity to have a real impact on issues that donors care about, making the case that philanthropy is the natural funder for such organizations, and attracting larger and longer-term gifts.

Philanthropy-focused funding models depend on multi-year philanthropic commitments, otherwise organizations may be financially vulnerable. This is particularly true for those doing equity, justice, and social reform work, organizations often led by people of color with lived experiences anchored in the communities their organizations serve. In those cases, philanthropy is a natural strategic partner—yet leaders of color still face distinct challenges in raising and sustaining philanthropic funding. For these leaders, the work continues. “Philanthropy should be willing not just to fund for a little while but to build a sustained and durable institution,” says McAfee.

Build Dedicated Capabilities and Infrastructure To Raise Your Natural Match Funding

We said earlier that most of the nonprofits that get big do one or two things exceptionally well. We want to emphasize that last part—exceptionally well. That means these organizations build a professional organization that is excellent at raising their dominant revenue category—and sometimes an important secondary category. They get very clear on what activities will bring in their natural match funding, then they hire, recruit, and contract for the capabilities needed to accomplish these activities.

DonorsChoose, for example, has developed a thorough understanding of how to connect with and cultivate its primary funding source, individual gifts under $10,000. “We try to make the online user experience as seamless as possible,” explains CEO Alix Guerrier. “Their first contact will be on the website and it needs to be an experience that is rewarding to them. Teachers will post pictures of what happened in class during the project.” The organization works hard to create more opportunities for matches between donors and projects. “People give to their local areas, places they have affinity towards—so geography is important,” says Guerrier. “We launched a map feature where you can zoom in and find projects.”

Each revenue category is unlocked by a unique set of assets and capabilities. For example, organizations successful at raising government funding are typically strong at lobbying, technical grant writing, and compliance. Organizations anchored by program service fees are focused on product development, pricing, and marketing. For additional detail on revenue categories and associated assets and capabilities, see Bridgespan’s “Funding Categories at a Glance.”

For its part, the Center for Sustainable Energy, whose dominant revenue category is state government, does not have the kind of development office that some may see as a model—someone who does individual giving, someone who does grants, maybe an events person or two. “That is not our business,” says CEO Goldenhersh. “We will not be able to accomplish our mission unless we compete in the market. We often go head-to-head with for-profit businesses. That’s our funding strategy.”

* * *

Our research on how US nonprofits get big underlines that, for the great majority of those which have grown to $50 million or more in annual revenue since 1990—and for those who aspire to grow to that scale—there is a clear roadmap. Focus on one or two revenue categories, seek funding that is a natural match for your organization’s work, and build dedicated capabilities and infrastructure to tap into the one or two revenue categories you’re focusing on.

Note on Methodology

To assemble our data set, similar to the 2007 study, we examined the most recent publicly available audited financial statement (or IRS Form 990) for each organization, which was from 2021 in most cases. We excluded several categories of nonprofits, including hospitals and universities and affiliates of national networks founded before 1990. We then grouped revenue into six categories—government, program service fees, corporate, philanthropy (foundation grants and individual gifts of $10,000 or more), individual giving under $10,000, and investment income. To gather data on CEO/executive director racial and ethnic identity, we emailed all organizations with publicly listed email addresses. In instances when we could not find an email address or did not hear a response, we looked at self-identifying information from public sources and excluded organizations for which we did not find definitive information. For further detail on our research methodology, see https://www.bridgespan.org/insights/how-nonprofits-get-really-big-2024.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Ali Kelley, Darren Isom, Bradley Seeman, Julia Silverman, Analia Cuevas-Ferreras & Katrina Frei-Herrmann.