The primary driving force behind the rapid integration of technology in education has been its emphasis on student performance (Lai and Bower, 2019). Over the past decade, numerous studies have undertaken comparisons of student academic achievement in online and in-person settings (e.g., Bettinger et al., 2017; Fischer et al., 2020; Iglesias-Pradas et al., 2021). This section offers a concise review of the disparities in academic achievement between college students engaged in in-person and online learning, as identified in existing research.

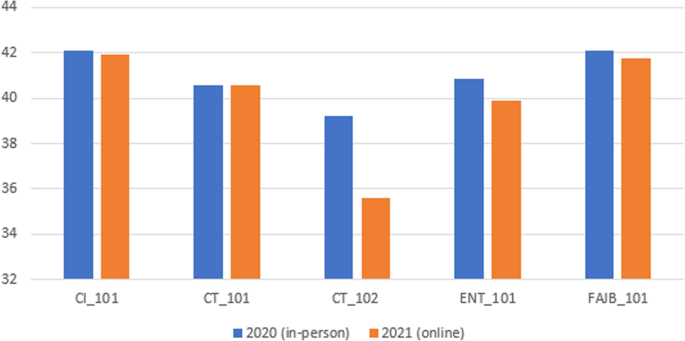

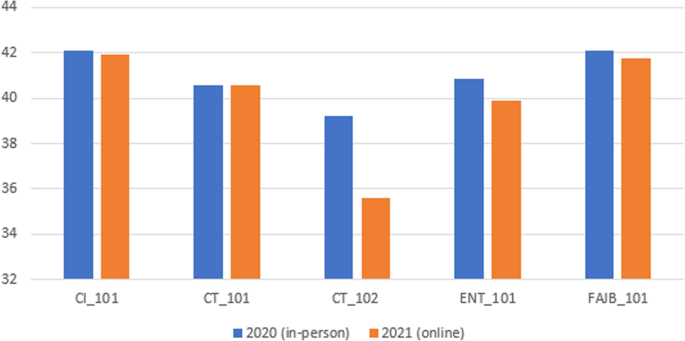

A number of studies point to the superiority of traditional in-person education over online learning in terms of academic outcomes. For example, Fischer et al. (2020) conducted a comprehensive study involving 72,000 university students across 433 subjects, revealing that online students tend to achieve slightly lower academic results than their in-class counterparts. Similarly, Bettinger et al. (2017) found that students at for-profit online universities generally underperformed when compared to their in-person peers. Supporting this trend, Figlio et al. (2013) indicated that in-person instruction consistently produced better results, particularly among specific subgroups like males, lower-performing students, and Hispanic learners. Additionally, Kaupp’s (2012) research in California community colleges demonstrated that online students faced lower completion and success rates compared to their traditional in-person counterparts (Fig. 1).

In contrast, other studies present evidence of online students outperforming their in-person peers. For example, Iglesias-Pradas et al. (2021) conducted a comparative analysis of 43 bachelor courses at Telecommunication Engineering College in Malaysia, revealing that online students achieved higher academic outcomes than their in-person counterparts. Similarly, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Gonzalez et al. (2020) found that students engaged in online learning performed better than those who had previously taken the same subjects in traditional in-class settings.

Expanding on this topic, several studies have reported mixed results when comparing the academic performance of online and in-person students, with various student and instructor factors emerging as influential variables. Chesser et al. (2020) noted that student traits such as conscientiousness, agreeableness, and extraversion play a substantial role in academic achievement, regardless of the learning environment—be it traditional in-person classrooms or online settings. Furthermore, Cacault et al. (2021) discovered that online students with higher academic proficiency tend to outperform those with lower academic capabilities, suggesting that differences in students’ academic abilities may impact their performance. In contrast, Bergstrand and Savage (2013) found that online classes received lower overall ratings and exhibited a less respectful learning environment when compared to in-person instruction. Nevertheless, they also observed that the teaching efficiency of both in-class and online courses varied significantly depending on the instructors’ backgrounds and approaches. These findings underscore the multifaceted nature of the online vs. in-person learning debate, highlighting the need for a nuanced understanding of the factors at play.

Theoretical framework

Constructivism is a well-established learning theory that places learners at the forefront of their educational experience, emphasizing their active role in constructing knowledge through interactions with their environment (Duffy and Jonassen, 2009). According to constructivist principles, learners build their understanding by assimilating new information into their existing cognitive frameworks (Vygotsky, 1978). This theory highlights the importance of context, active engagement, and the social nature of learning (Dewey, 1938). Constructivist approaches often involve hands-on activities, problem-solving tasks, and opportunities for collaborative exploration (Brooks and Brooks, 1999).

In the realm of education, subject-specific pedagogy emerges as a vital perspective that acknowledges the distinctive nature of different academic disciplines (Shulman, 1986). It suggests that teaching methods should be tailored to the specific characteristics of each subject, recognizing that subjects like mathematics, literature, or science require different approaches to facilitate effective learning (Shulman, 1987). Subject-specific pedagogy emphasizes that the methods of instruction should mirror the ways experts in a particular field think, reason, and engage with their subject matter (Cochran-Smith and Zeichner, 2005).

When applying these principles to the design of instruction for online and in-person learning environments, the significance of adapting methods becomes even more pronounced. Online learning often requires unique approaches due to its reliance on technology, asynchronous interactions, and potential for reduced social presence (Anderson, 2003). In-person learning, on the other hand, benefits from face-to-face interactions and immediate feedback (Allen and Seaman, 2016). Here, the interplay of constructivism and subject-specific pedagogy becomes evident.

Online learning. In an online environment, constructivist principles can be upheld by creating interactive online activities that promote exploration, reflection, and collaborative learning (Salmon, 2000). Discussion forums, virtual labs, and multimedia presentations can provide opportunities for students to actively engage with the subject matter (Harasim, 2017). By integrating subject-specific pedagogy, educators can design online content that mirrors the discipline’s methodologies while leveraging technology for authentic experiences (Koehler and Mishra, 2009). For instance, an online history course might incorporate virtual museum tours, primary source analysis, and collaborative timeline projects.

In-person learning. In a traditional brick-and-mortar classroom setting, constructivist methods can be implemented through group activities, problem-solving tasks, and in-depth discussions that encourage active participation (Jonassen et al., 2003). Subject-specific pedagogy complements this by shaping instructional methods to align with the inherent characteristics of the subject (Hattie, 2009). For instance, in a physics class, hands-on experiments and real-world applications can bring theoretical concepts to life (Hake, 1998).

In sum, the fusion of constructivism and subject-specific pedagogy offers a versatile approach to instructional design that adapts to different learning environments (Garrison, 2011). By incorporating the principles of both theories, educators can tailor their methods to suit the unique demands of online and in-person learning, ultimately providing students with engaging and effective learning experiences that align with the nature of the subject matter and the mode of instruction.