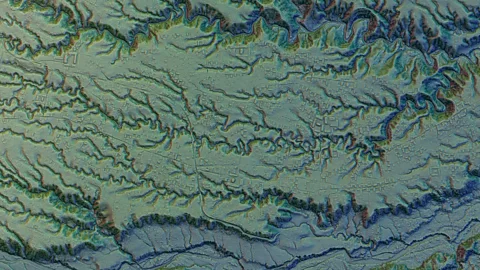

KalypsoWorldPhotography/Alamy

KalypsoWorldPhotography/AlamyThe unearthing of an immense network of cities deep in the Ecuadorean Amazon is proving that the world’s biggest rainforest was once a thriving cosmopolitan hub.

“Let me ask you something,” said archaeologist Stéphen Rostain. “What do you know about the history of the Amazon?”

I thought about it for a moment, and just as I opened my mouth to respond, Rostain let me in on a little secret: “You know nothing, because the history that we think we know is wrong. It’s a history made by so-called chroniclers that rarely saw what they described. It’s a history of lies. We know a little bit from colonial times, but it’s a story of exploitation of land, torture and slavery. It’s not a beautiful history. But this, the discovery of a vast urban cradle lets us better understand the first actors of this history: the Indigenous people. It forces us to rethink the entire human past of the Amazon.”

The previous day, Rostain and his team had published the results of a study that was nearly 30 years in the making, and that sent shockwaves around the world.

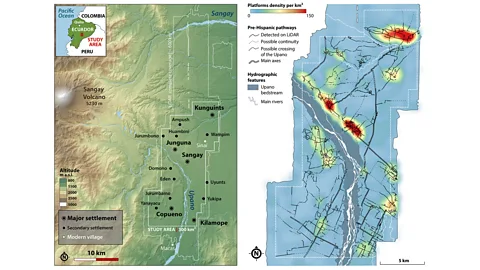

Using airborne laser-scanning technology (Lidar), Rostain and his colleagues discovered a long-lost network of cities extending across 300sq km in the Ecuadorean Amazon, complete with plazas, ceremonial sites, drainage canals and roads that were built 2,500 years ago and had remained hidden for thousands of years. They also identified more than 6,000 rectangular earthen platforms believed to be homes and communal buildings in 15 urban centres surrounded by terraced agricultural fields.

Antoine Dorison and Stéphen Rostain

Antoine Dorison and Stéphen Rostain“It was really a lost valley of cities,” said Rostain, the director of investigation at the National Centre for Scientific Research in France. “It’s incredible.”

According to Rostain, the most striking aspect of this urban cluster, which is located in eastern Ecuador’s Upano Valley, is its astonishing road network. The cities’ streets were engineered to be perfectly straight, connecting at right angles with one another and linking the different cities like a prehistoric highway. The largest were 10m wide, with one extending 25km. “Given the hilly terrain, this road network was even more advanced than modern ones,” Rostain said.

This forgotten network of cities is not only believed to be more than 1,000 years older than any other known complex Amazonian site, but its staggering size and level of sophistication suggests a highly structured society that appears to be even larger than the well-known Maya cities in Mexico and Central America.

According to Rostain and his team, beginning in roughly 500 BCE, the Kilamope and later Upano cultures begun building their homes on raised platforms that were organised around plazas. The size of this early city covers an area that’s comparable to Egypt’s pyramid-studded Giza Plateau. Dating suggests these societies thrived and expanded for roughly 1,000 years until the sites were mysteriously abandoned between 300 and 600 AD – a period roughly contemporaneous with Ancient Rome.

Antoine Dorison and Stéphen Rostain

Antoine Dorison and Stéphen RostainWhile it’s difficult to estimate how many people lived in these connected cities at any one time, archaeologist Antoine Dorison, who worked with Rostain on the Lidar findings and co-authored the paper, said that at its peak, it could have been home to as many as 30,000 people. Other estimates suggest the number could have been in the hundreds of thousands. If true, this would make it comparable with the estimated population of Roman-era London.

“This discovery has proven there was an equivalent of Rome in Amazonia,” Rostain said. “The people living in these societies weren’t semi-nomadic people lost in the rainforest looking for food. They weren’t the small tribes of the Amazon we know today. They were highly specialised people: earthmovers, engineers, farmers, fishermen, priests, chiefs or kings. It was a stratified society, a specialised society, so there is certainly something of Rome.”

And yet, were it not for two priests, the world would never have known about this long-lost “Amazonian Rome”.

As Rostain explained, in the 1970s, a local priest named Juan Bottasso stumbled upon a strange-looking mound built atop a platform in the Upano Valley. Soon after, Bottasso was visited by another priest from Quito named Pedro Porras and Bottasso said to him, “I want to show you something.” The two rode on horseback to the mound, and Porras, apparently curious about what he’d seen, organised a crude excavation of it and published his findings in an Ecuadorean paper. The site was then forgotten for roughly 15 years until Rostain, who had been excavating a Maya site in Guatemala in the 1980s, uncovered the priest’s publication and set out for Ecuador.

Stéphen Rostain

Stéphen RostainWith the help of an Ecuadorean colleague, Rostain began excavating the mounds in 1996. Two years later, his colleague abandoned the project (“Not everybody is in love with working in Amazonia,” Rostain said), but Rostain continued hacking his way through the jungle for seven more years, uncovering roads, additional sites and what he thought were hundreds of mounds. “It was different than anything I’d seen before,” he said. “In the Amazon, they don’t build with stone, like in Maya or Inca territory. It was only earthen architecture.”

Rostain returned to live in Ecuador in 2011, and in 2015, Ecuador’s National Institute for Cultural Heritage funded an aerial survey of the valley with Lidar, which has been transforming how archaeologists conduct research in jungles and revealing previously unknown evidence of Maya and other pre-Columbian societies. When Rostain and Dorison received the data in 2021 and began poring through it, Rostain realised he was completely wrong: “There weren’t hundreds of mounds, but at least 6,000 and probably many, many more.”

One of the most intriguing questions Rostain and his colleagues have been trying to understand is what led this society to engineer perfectly straight roads through the region’s mountainous topography. “Why would you build these straight roads five metres deep when you can easily walk through the hills?” Rostain asked. “I think they built them to imprint their identity, their relationship with the Earth in the earth. They are symbolic roads, like other roads in the Andes [notably the Inca’s famed Qhapaq Ñan, which is still considered by many Inca descendants as a living road today].”

Rostain and his team have also identified several other features from the Upano cities that have survived what he calls the pre-Columbian world’s “catastrophic contact” with the Spanish. The cities’ orthogonal plot system of drained fields and terraces mirrors that which is still used by the Indigenous Cariña people of Venezuela. Analysis of starch grains from the many decorative and painted vessels found reveal that the area’s earliest residents cultivated beans, manioc, sweet potatoes and maize, just as Indigenous residents in the area do today. In fact, the Upano Valley’s highly fertile volcanic soil (which might have allowed these societies to thrive, and could have led to its sudden collapse if the nearby Sangay volcano erupted) still enable modern-day Indigenous farmers to harvest maize three times a year. And some micro-traces recovered at the sites are identical to those of modern-day chicha (fermented corn beer).

“I am deeply impressed by the profound wisdom of the Amazonian Indigenous people,” said Carla Jaimes Betancourt, an archaeologist specialising in the Americas at the University of Bonn. “Their remarkable understanding of their environment, coupled with their insightful practices for modifying the landscape, has created a unique biocultural legacy that endures to this day and is our duty to preserve. I believe that these cities will serve as examples, offering inspiration for the future through their harmonious integration with the natural world.”

Local attractions

The Upano Valley is a growing eco-tourism destination. The town of Macas is a good place to base yourself for rafting, hiking and hot spring excursions. The nearby Sangay National Park is a Unesco World Heritage Site home to three volcanoes, dozens of lagoons and a stunning amount of biodiversity.

Like Machu Picchu and so many of the famed Maya sites, Rostain is confident that travellers will one day be able to experience the Upano Valley’s cities for themselves, but as he said: “You have to be patient. It’s still very much a forgotten place with very few tourists.” Yet, when that day comes, he says visitors will be in for a treat.

“It’s a beautiful landscape,” he said. “You have the [Upano] river that cuts like a knife in the ground and is 2km wide. There are 100m-tall vertical cliffs and forest and 30km away, you can see the towering Sangay volcano. I understand why the Upano people chose this place [then], and why they choose this place [today].”

For now, Rostain is simply happy to have given something back to Ecuador during this tough time in its modern history. “I’m in love with Ecuador and I think such a discovery gives a little bit of pride to the Ecuadorean people,” he said. “For so long, they have suffered a little bit of comparison with Peru. Ecuador didn’t have their Rome, and now I think they’ve got it.”