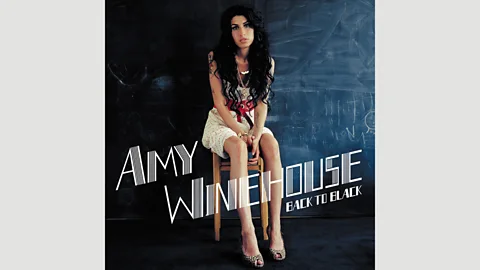

Alamy

AlamyBack to Black turns 10 – though it was raw and confessional it didn’t reveal the whole truth about the artist’s struggles, writes Fraser McAlpine.

The factors that combine to create a world-beating album are often whisper-soft, tissue-thin and impossible to recapture. Talent plays a key role, but so does timing, judgment and a great deal of good luck.

In the case of Amy Winehouse’s Back to Black, released 10 years ago today, the talent was undeniable, but her personal judgement was questionable even when her artistic decisions were beyond reproach; her perfect timing was ultimately a mixed blessing; and whatever luck surrounded her quickly flip-flopped from bad to good, and then back again with renewed vigour.

The autobiographical stuff has been raked over enough: a girl met a boy. He was in a relationship he didn’t want to end, but the attraction between them was too strong to overcome. His ambivalence fuelled her easily triggered feelings of low self-esteem; from which the only escape was to drink or take drugs until something felt different.

Island

IslandThis lead to a series of bleak, drunken episodes and ultimately some kind of intervention, in which friends and family tried to encourage her to look after herself. Deep in the throes of addiction and with the skills of denial developed from a lifetime hiding an eating disorder, she bullishly insisted she was fine, while desperately throwing everything, utterly everything, into the lyrics for her new album as her sole salvation.

It’s at this point the talent takes over. The 11 songs Amy Winehouse wrote for Back to Black are a poetic response to chaotic feelings. Sometimes they are philosophical and poised – as in Love is a Losing Game – sometimes they’re stroppy and tough. Her bruised voice makes order out of disorder, giving her – and therefore her audience – a feeling of control over heartbreak, and a way to deal with some extraordinarily potent emotions by detailing her darkest, most grimy actions with a forensic, gleeful eye for detail. One listen to You Know I’m No Good is enough to put anyone further into the picture than they may wish to venture.

And that true-life detail is one of the key factors fuelling the success of the album. While Amy was a colossal jazz, soul and gospel fan, using the emotive heft of the music of the early 20th Century as the stylistic base for her own songwriting, her lyrics were inspired by the brutal honesty and toughness of hip hop. It’s an influence she was more than happy to let show, especially in Me & Mr Jones, with references to Slick Rick and Nas, and using flowery profanity that never troubled the song sheets of Ella Fitzgerald or Billie Holiday.

Another key factor, and a slightly more contentious one, is the sumptuousness of the arrangements. Both Mark Ronson and Salaam Remi sought to place Amy’s words into plush musical backing. While Ronson’s focus was to create a full-scale Motown revue, bringing in the Dap-Kings to create arrangements based on those used in records by The Supremes and The Temptations – particularly in Back to Black – Remi drew from a slightly broader pool of black music for inspiration. While his Tears Dry on their Own is cut from a similar cloth, he also provided the torch song backwash for Some Unholy War, and the twinkling Lovers’ Rock for Just Friends.

Alamy

AlamyUltimately both producers attempted to match the gut-punch of Amy’s lyrics with the undeniable vitality of soul, which made her bleak tales seem more accessible and in no small measure contributed to the album’s eventual popularity.

It could be argued that this sweetening detracted from the songs’ meanings, burying the poetry and truth of Amy’s words under a gloss of immaculately rendered retro-soul, rather than sharpening up all of her raw edges. But it’s worth noting that the sampling or fastidious recreation of the sound of old records to make new ones fitted perfectly with Amy’s love of both hip hop and classic soul. It gave her musical armour.

Alamy

AlamyThe cornerstone of this approach was Rehab, the album’s first single and the song which ensured that Amy Winehouse would remain a media sensation for the rest of her life. It’s a song as a perfect moment, the glorious cussedness of a cornered Ray Charles reborn in the mouth of a frustrated, heartbroken woman from London. And despite that song generating a million cheap jibes against its own singer in the months to come, its power lies in both the rebellious two-fingered salute of the moment she wrote it, and the ruthless commercial exploitation of her personal life that immediately followed.

Just before the moment of inspiration struck, Mark Ronson had been talking to her about an attempt her dad made to get her to deal with her alcoholic blackouts. In a later interview with BBC Radio 1, Mark revealed that she had said “‘He tried to make me go to rehab and I was like, ‘Pfft, no no no.'”, immediately hearing the song blossom in his head, and recognising this made him a poor friend but a great producer. “I mean I’m supposed to be like, ‘How was that for you?’ and all I’m like is, ‘We’ve got to go back to the studio.’” Honesty was aided by artistry, and the Amy Winehouse theme song was born, for better and worse.

That’s one of the key reasons Back to Black stands alone next to almost every other album released in 2006. Plenty of artists were exploring dusty old jazz ballads or retro soul, and a good deal of them would happily lay claim to be writing honest songs. Adele would soon come along and take over the world with a similarly winning mix of rhythm and blues and romantic damnation, leaving Joss Stone and Duffy wondering what she has that they don’t.

But very few of them were living a life as extreme as Amy’s, and still fewer would have admitted every unflattering bruise and blemish, artfully or otherwise. Maybe they could’ve written a Tears Dry on Their Own, but only Amy Winehouse could have written a song as self-lacerating or vulnerable as Back to Black, all the while packing her romantic suicide note with bitter wisdom and hard-boiled wit.

Alamy

AlamyThere’s an argument that this honesty was just a smokescreen, a way of hiding a worse truth in plain sight, under a barrage of grotty reportage. Yes she was heartbroken, yes she was drunk, yes she had some leftover issues from her childhood and yes she was capable of extreme behaviour, but while she does mention her lover, her boozing, her drug use, her various push ‘n’ pull escapades and even her dad in song, there are no Amy Winehouse lyrics about food or eating disorders, and that has to be a deliberate choice on her part.

But even without that hidden narrative, as an album Back to Black speaks to so many people because we all share the interior monologue that we’re grotesque and unworthy of good fortune. Even without having experienced a fraction of the things listed in the album’s lyric sheet, we all carry the suspicion that we are messy, flawed individuals who feel like we can’t do right for doing wrong. If love is a losing game, what we all need is the advice of someone who has gone for broke, gambled everything they had, and lost.